Category: Highlight

-

Medieval Institute 3D Modeling Workshop

This spring, the Digital Medieval Studies Institute, a full day of programming on digital scholarly methods for medievalists and pre-modernists, was hosted by Harvard and BC’s McMullen Museum. Several of the workshops were hosted on BC’s campus, including the session on photogrammetry led by Antonio LoPiano. This session took place within the Ricci Institute for…

-

Say Hello to the DSG Student Workers

We have three wonderful undergraduate student workers who assist with DSG projects each and every week: Amen Amare, Caleb Lee, and Nathanael Choi. Because they work in the Digital Studio space, these three are also available to help other students with software on Digital Studio computers. Amen is an Economics major who hopes to work…

-

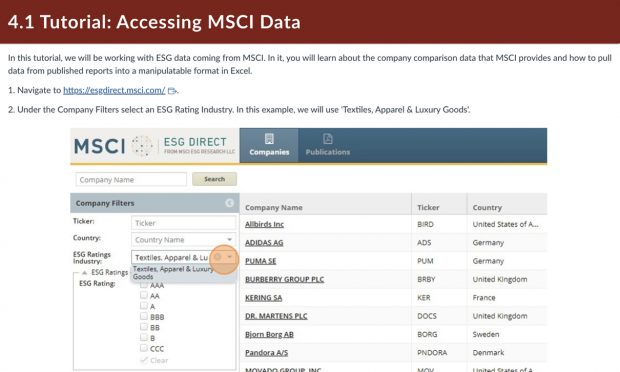

Engaging with Data

A key element of Digital Scholarship is engaging with data. As our team’s data services specialist, I want to move away from data being viewed as enigmas that we have to wrangle with and understand in isolation. Rather, they should work in tandem with theory and context in a learning environment. In a recent collaboration…

-

In Digital Scholarship, Collaboration is Key

The Digital Scholarship Group encourages members of the BC community to consider incorporating Digital Scholarship (DS) methods into their research. Whether you know it or not, you engage in digital scholarship when you integrate new, digital sources of data into your research, use computing tools to process that data, or leverage digital platforms to present…

-

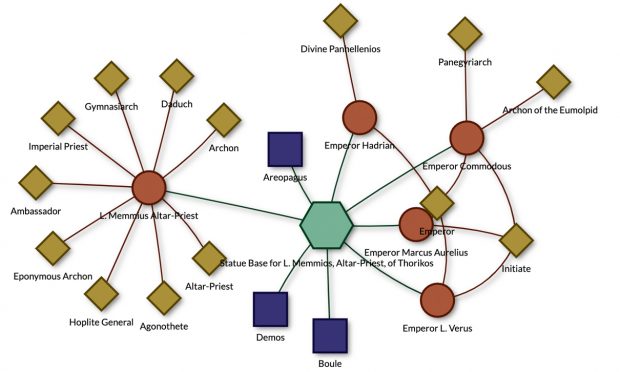

Building Data Tools for Exploring the Past

When most people think about data analysis and building databases, they don’t typically imagine using them for literature and music scholarship. But that’s precisely the work I’ve been doing this semester. With Professor Maia McAleavey, BC professor of English, I have been building an interactive web portal for a research project exploring the composition of…

-

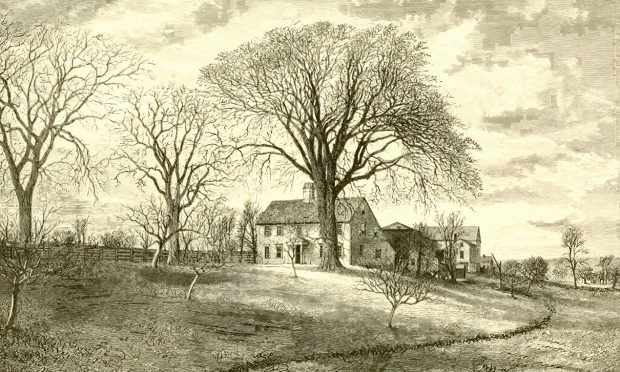

Finding Bradstreet: Going From the Material to the Digital

As an archeologist, I have excavated everywhere, from the deserts of Jordan to the hills of Tuscany in pursuit of cities, villas, and tombs, but never before have I dug to discover the life of a poet. That’s why I jumped at the chance when Dr. Christy Pottroff, BC Professor of English, invited me to…

You must be logged in to post a comment.