Category: Projects

-

It’s a Bird! It’s a Project! It’s a Bird Project!

You may have observed some seemingly odd experiments if you’ve walked past the Digital Studio this semester. What are all those flashing lights, and are those… birds? In reality, what you’re witnessing is an important contribution to undergraduate pedagogy here at BC. Hands-on time with specimens is a critical component of any Biology curriculum, especially…

-

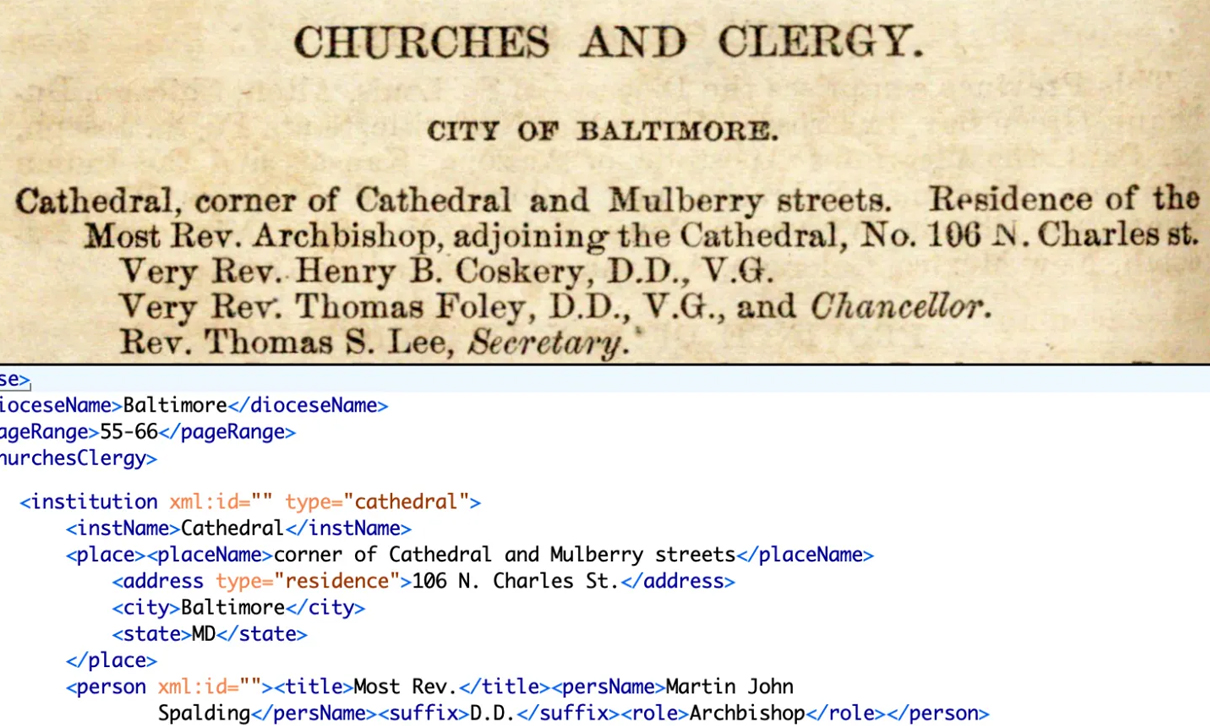

Catholic Almanacs Project Getting Off The Ground

One unexpectedly rich source about the history of Catholicism in the United States is a series of Catholic almanacs containing extensive data about US dioceses throughout the nineteenth century. Today, the almanacs are housed at Boston College Libraries, and some are digitized and made available by Villanova, HathiTrust, and the Internet Archive. Now, as part…

-

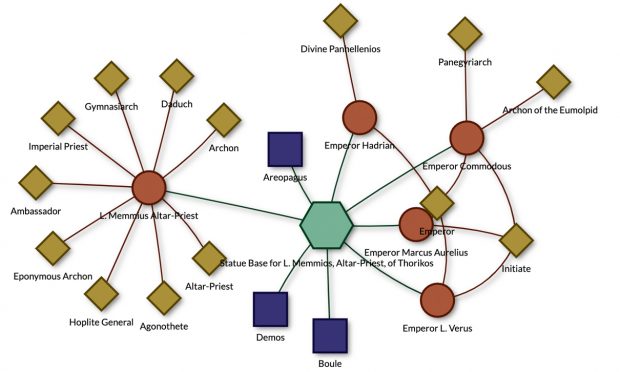

Building Data Tools for Exploring the Past

When most people think about data analysis and building databases, they don’t typically imagine using them for literature and music scholarship. But that’s precisely the work I’ve been doing this semester. With Professor Maia McAleavey, BC professor of English, I have been building an interactive web portal for a research project exploring the composition of…

-

Finding Bradstreet: Going From the Material to the Digital

As an archeologist, I have excavated everywhere, from the deserts of Jordan to the hills of Tuscany in pursuit of cities, villas, and tombs, but never before have I dug to discover the life of a poet. That’s why I jumped at the chance when Dr. Christy Pottroff, BC Professor of English, invited me to…

-

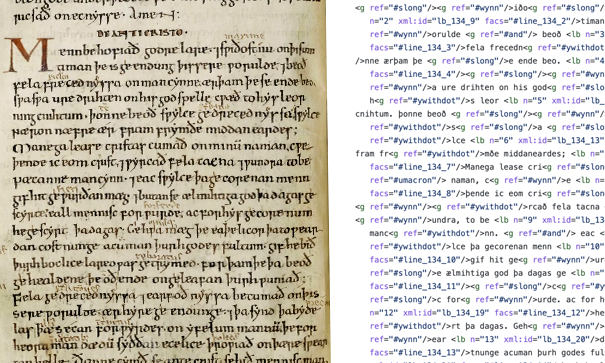

Digital Medieval Studies

I talk about creating my DH capstone project. How DH Has Helped Me Make Sense of My Field Early in my graduate studies, when I took the Digital Humanities Colloquium at Boston College, the professor had us read a series of definitions of “the Digital Humanities” to introduce us to the scope of the work…

-

New digital resource: 19th century petition letters for Jesuit mission assignments

A set of original handwritten letters housed in the Jesuit Archive in Rome has been scanned and transcribed and is now available freely on the web for research and study. A collaboration between Boston College Libraries, the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies and Emanuele Colombo of DePaul University, the Digital Indipetae Database offers an ordered…

You must be logged in to post a comment.